Dirk Braeckman, one of the most prominent art photographers in Belgium, plays with such photographic parameters as light, focus and framing in order to create highly individual images.

His black and white photos picture lost moments and corners and reveal the blind spots in our traditional perception.

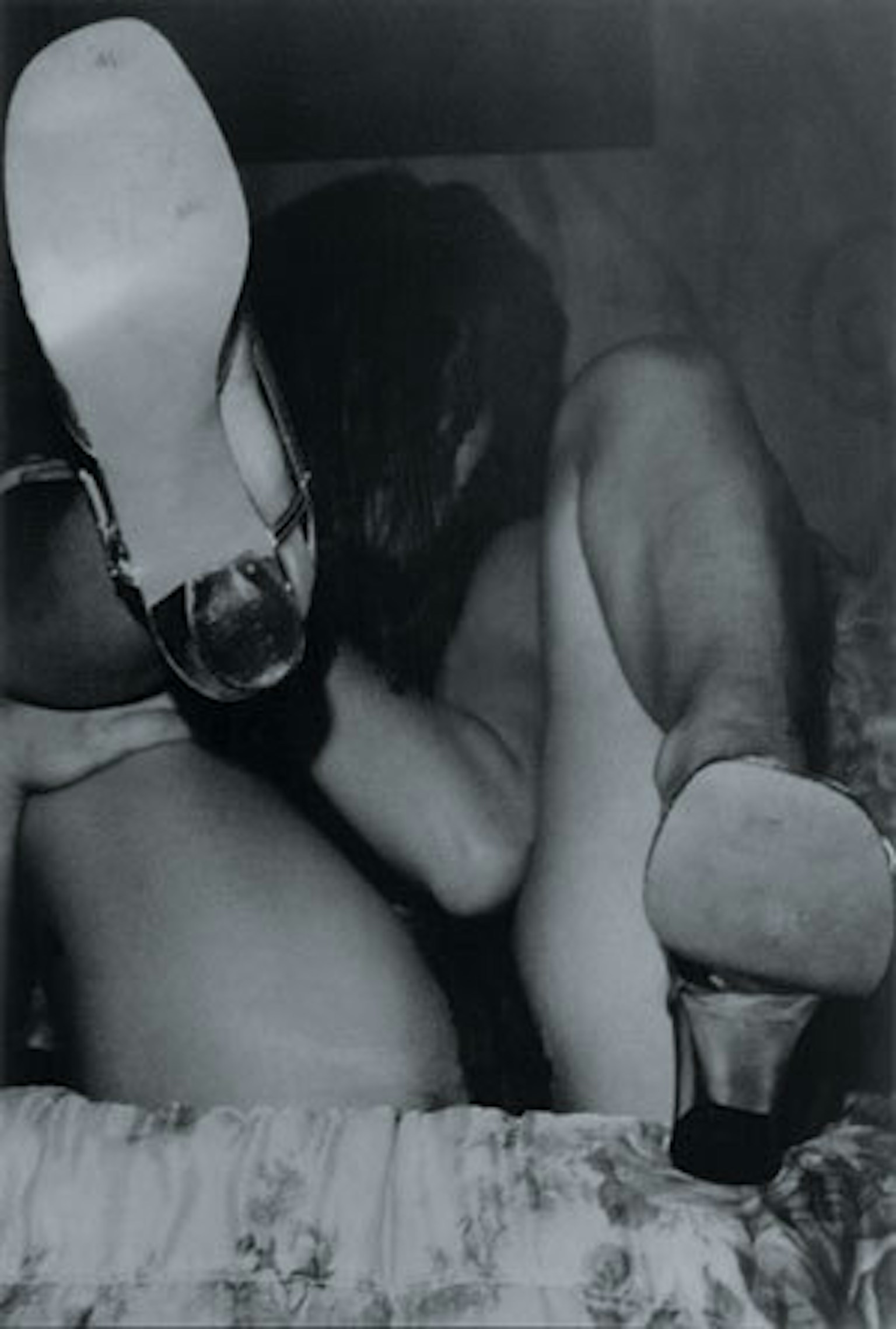

Dirk Braeckman (°1958 Eeklo) is without doubt one of the leading artist-photographers in Belgium. Having studied at the Academy in Ghent from 1977 to 1981, he has already accumulated a major record of international exhibitions and prizes. He also teaches at the art college in Antwerp. Braeckman’s early work consisted primarily of portraits of people he knew, mainly women. They were portrayed spontaneously, unposed, but always with the accent on fragility and every possible sign of life and being shackled to life, ‘abîmées par la vie’ [damaged by life]. Eroticism and ‘tristesse d’être au monde’ [the sorrow of being in this world] were never far away. In the next phase of his work, the models were increasingly veiled in anonymity. There is a fascinating air of elusiveness and incomprehensibility, which had in fact already been there in the earlier portraits, but which did not tell the viewer much more than the name of the model and the fact that she was there. Objects gradually started to come to the fore. It was not so much the model that drew all the attention as trivial things like underwear and stiletto heels. And then, quite clearly after his stay in New York in 1994, the surroundings, the room itself ultimately stepped into the foreground. Braeckman developed a subtle idiom of form, spontaneous and minimal, which charges a bedroom, a shower stall, a meeting room or anywhere else with significance, frequently strange and unsettling. Still.’Abîmées par la vie’ all over again. This exhibition shows a selection of large format pictures from the last six years. They can be seen as ‘portraits’ of rooms. Just like portraits of people - see his early work - the pictures say something about themselves and their surroundings, without simply holding up a mirror to them or offering a banal reproduction. The photos are themselves, they are what they are, they do not depict anything for the sake of it. The artist does not tell us how to look at these pictures. What he finds essential is the act of taking the picture. In this respect too the photos are self-supporting. But it is precisely at this point that it all comes together: the act is impossible without the actor.

Braeckman sees his camera as an extension of his body: ‘je photographie depuis mon corps’ [I photograph from my body]. The pictures are unmistakably tinged by Braeckman’s own observation and reflection. These black and white photos illustrate lost moments and corners and reveal the blind spots in our traditional notion of observation. Again there is no question of flatly depicting things. He also talks of moments of fusion with his surroundings, ‘I get into a state of mind that makes me anticipate the surrounding space, and the need arises to capture this dialogue with reality’. Braeckman never uses extreme angles of view and never uses a tripod. The photos are taken from where he is standing or sitting, without staging or taking any account of any norms. However, in addition to this great involvement in the act, distance also has a part to play. This aspect can be illustrated very well by Braeckman’s way of handling negatives: ‘After a shoot I look at the negative purely as it is, meaning as a formal and material support for pixels. This means that I make a complete abstraction of the picture, which also already allows me to see at this stage whether the image is right or not’. In this way, such photographic parameters as light, grey tones, focus and framing are of huge importance in supporting the spontaneous image.