Self Self

10.Jan.04

Johan Tahon is no stranger to this museum and has created new sculptures for several of its exhibitions.

In addition, the four of his works in the SMAK collection are evidence of a long and positive relationship between artist and museum. For the imposing but difficult Kunst Nu space, Tahon has very deliberately chosen a restrained show entitled 'Self Self'.

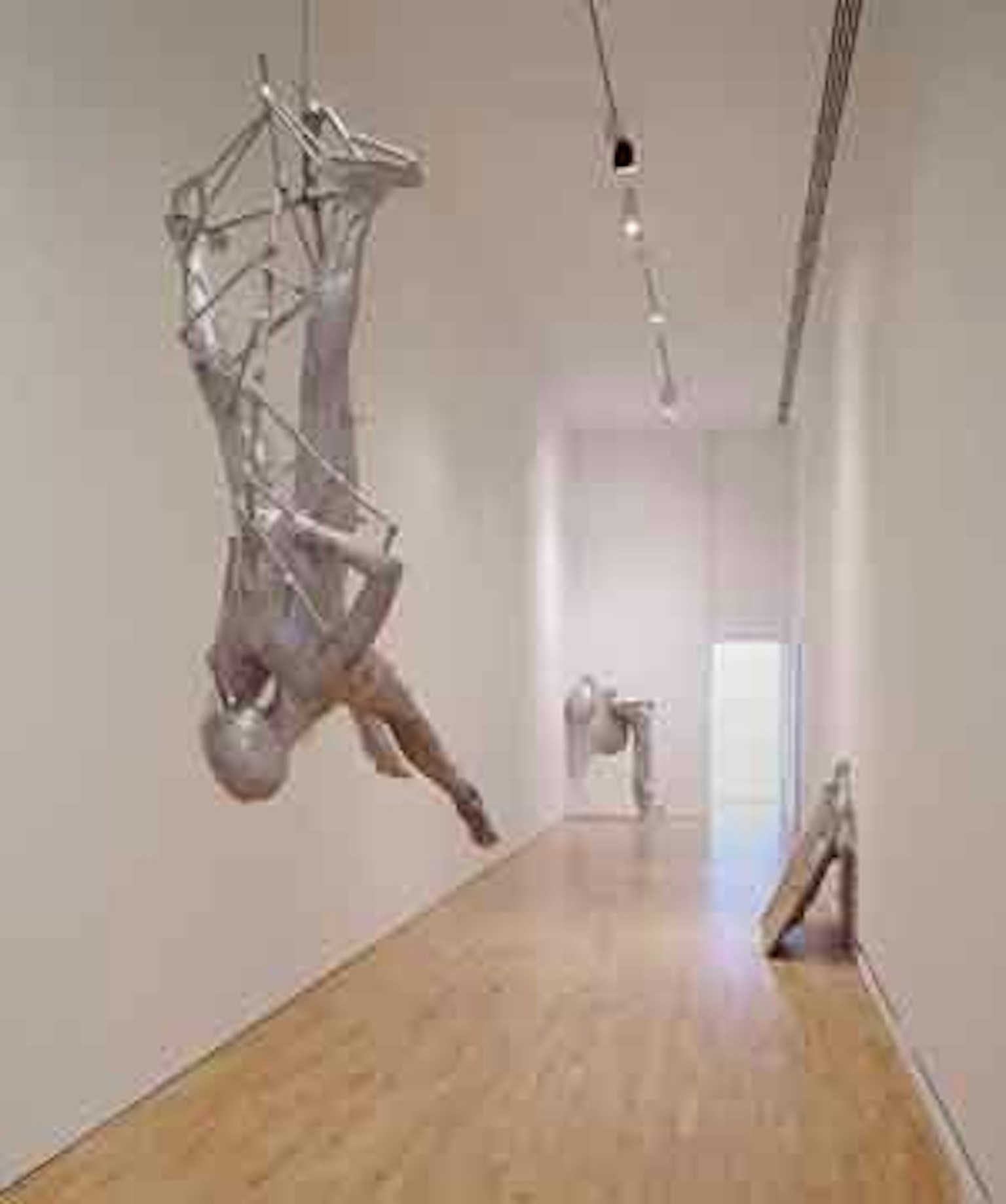

Up to now, Tahon’s work has been primarily associated with heavy plaster sculptures of twisted anthropomorphic figures. It is as if they emerged from a searching and agitated soul. The use of this particular material gives these sculptures an extra dramatic eloquence. Tahon’s work appears to have reached a turning point. In recent years he has developed a highly personal and recognisable style. He very recently found the freedom to experiment with new materials. Although little has changed in the basis of his work, these new materials nevertheless cast a new light on his sculpture. At an exhibition shown last summer at his home base in Ostend, Tahon had already showed sculptures in polyester. For the SELF SELF exhibition he is now, for the first time, showing works cast not in plaster but entirely in aluminium. This makes his sculptures look increasingly ephemeral. Whereas his previous works, however small they may have been, often seemed subject to material weight, and therefore to extreme melancholy, in these new works Tahon achieves a perfect balance between lightness and weight. In his quest for a material mirror for the soul, the artist quite deliberately left the nails and pins, the stubborn remnants of the casting process, as barbs. Nor has he sawn the mould funnels and technical structures off the sculpture. This makes them even more distorted – the hanging sculpture looks like a figure that is becoming increasingly intertwined with a network of branches – but at the same time, Tahon is here showing precisely that this is a quest, a process that is not complete and probably never will be. It is perhaps in exactly this way that he touches on the essence of art.

On the basis of his imagination and emotional experience, the artist creates a sculpture to which he is compelled to give shape. The artist has to try to bring dead material to life, to find the right form and proportions. The work of art must become the bearer of his imagination and must literally become an image. By making no attempt to hide the technical and material struggle, he makes it clear to the viewer that this has nothing to do with reality, but an illusion of reality, a unique dreamworld. This illusionary aspect is here undoubtedly enhanced by the shine of the aluminium. These sculptures may at first sight appear more remote, cooler, icy and even more threatening. But the danger lies not so much in the sculpture itself. Near the middle of the hall lies a convex sheet. Its surface is rough, with bulges. In addition, at the top, there is a network of lines, thick and thin. However, in the middle of the convex surface a small area of aluminium has been polished. Of all Tahon’s works this is the most abstract, the human figure seemingly entirely absent. It is however precisely in the polished part that the viewer sees his reflection, unrecognisable as it may be, and in this way the human figure always fleetingly turns up again. In this sense, it is impossible to interpret Johan Tahon’s sculptures purely as materialised images of the soul; they are rather steps in that direction. In addition, the viewer ultimately finds himself alone in the company of living beings, who in a certain sense form a very real reflection of an elusive, dynamic and constantly evolving reality.