This exhibition combines two travelling shows by the Belgian artist Michael Borremans (b. 1963), one of drawings, the other of paintings.

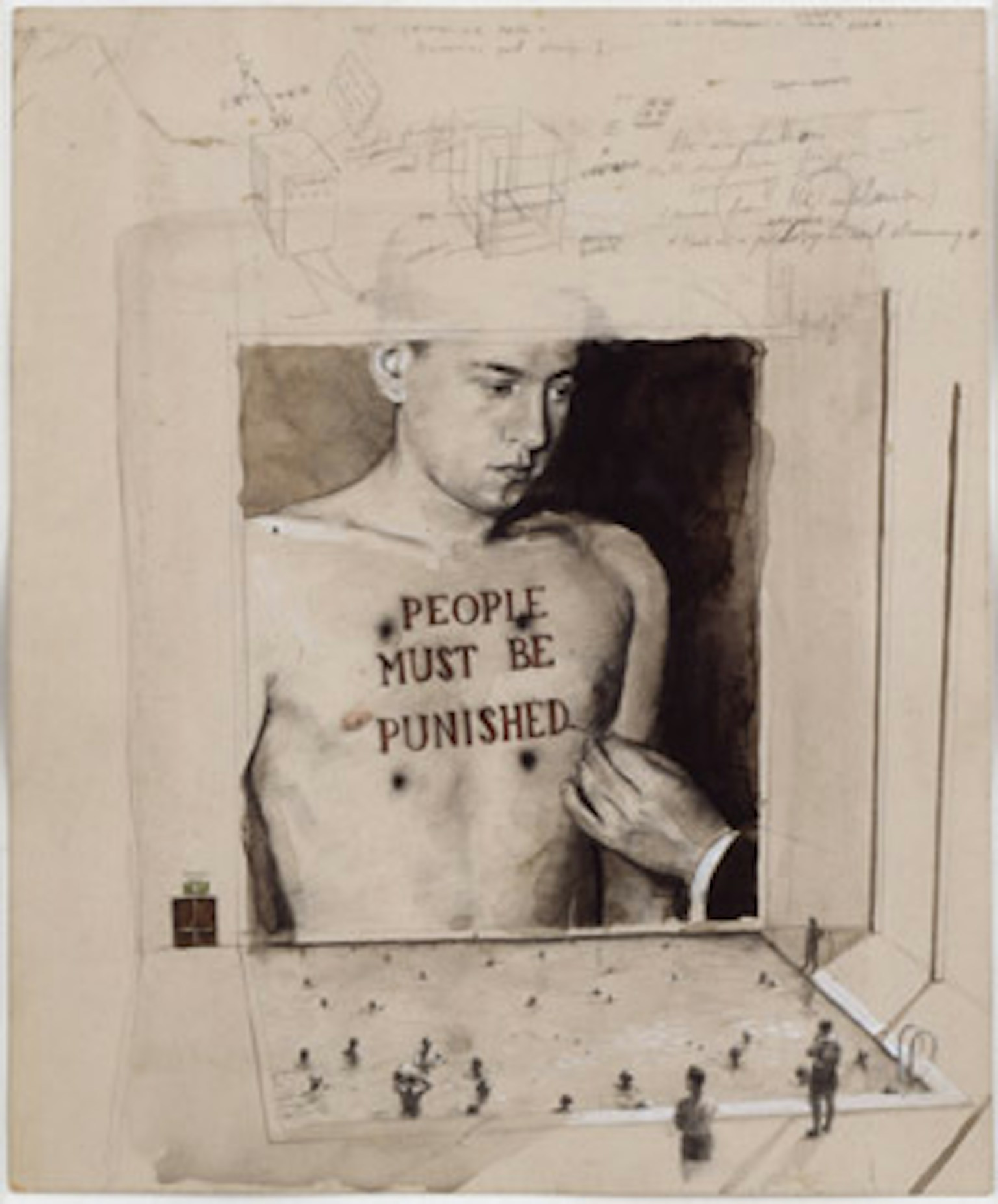

Michael Borremans: drawings Michael Borremans (b. 1963, Geraardsbergen) is meticulous and guarded when it comes to his drawing. He meticulously creates insinuating drawings, and guardedly sees to it that no one is able to read any all-embracing intention into these drawings. He has the same distaste for the story behind the illustration as for ‘the distortion of reality with which the mass media bombard us every day’. In his drawings, Michael Borremans regularly reflects on contemporary mass culture. In his small drawings he brings the viewer face-to-face with the ‘historical illusions’ that underlie present-day society, and shows us the deceit and indifference of the world around us. His work is concerned with the illusions he perceives around him, illusions about political choices, personal freedom and the individual’s ability to act in this complex world. In order to communicate the illusions to the viewer as clearly as possible, he lards his drawings with a beguiling aesthetic and a degree of provocation. Explicit references to art history and cultural tradition play a very important part in this. His drawings include a variety of genres such as the portrait, the bust, the death mask, the monument and the memorial. In addition to this he also refers to those places where works of art are usually shown, such as the studio, the museum or public space. Lastly, he also reflects on the different ways of staging art that were developed in the course of recent art history: the diorama in the 19th century, photography before the digital era, and the large video projections that one encounters at the present time. In addition, the question of reality and illusion runs like a thread through these drawings. Borremans again and again concerns himself with the distance between what we call reality and artistic fantasy or imagination. This is clearly to be seen from the fact that in his drawings he regularly portrays the viewers themselves as small figures on pedestals, almost artificial representatives of the work’s real viewers.

This contrast between reality and fantasy is also expressed in Borremans’ own perception of his drawing. He sees them as a sort of proposal for interventions or installations in public space. The execution of these drawn preliminary studies will however never reach the stage of ‘actual’ reality. Since he invariably classes public interventions as ‘acts of aggression’, he prefers to ‘limit’ its execution to a model. By playing with this idea as such, Borremans thus very consistently keeps to the very thin line between reality and fantasy that is so characteristic of his work. In addition to these aspects of Borremans’ drawing, time and history themselves also play a crucial part. He makes regular use of early sources of images on which to base his drawings. In most cases they are 19th-century photographs, and magazines and picture books from the thirties to the fifties, which he finds either in their original form or on the Internet. He may for example show the clothing and hairdressing fashions of the time, which makes the work seem in a way sincerely retrospective. At the same time the age and aesthetics of these sources of images seems to be transferred to his drawings by means of the colours too. Borremans uses images that are available in massive numbers, seeking out his own pictures and thereby succeeding in bridging the gap between the awareness of an historical past, a cultural tradition, and the problems of the present day. In terms of form and style, Borremans’ drawings display quite explicitly the influence of his former studies in printmaking and photography: they evolve very slowly. Each drawing is meticulously composed, and the artist repeatedly allows his drawing hand to return to the surface itself, in order to continue correcting and deepening it layer by layer. Working cautiously like this, Borremans reveals his affinity for the Northern tradition of miniature painting and the drawings of the old masters. The content underlying these formal choices also demonstrates very clearly Borremans’ roots in the Belgian painting tradition. Like the work of his compatriots James Ensor, Félicien Rops, René Magritte and Thierry De Cordier, Borremans’ hand reveals the surrealistic tendency to avoid logical associations. In terms of material and appearance his drawings are highly suggestive and intuitive. He uses almost any sort of material as a possible support for his work. He draws on torn-open envelopes (with postage stamps still attached), covers torn off books, the backs of old photos, pages from calendars, the remains of picture mounts, and so on. In this way he is also emphasising his affinity with history. Each support has its own history and displays the pronounced external marks of it, which the artist incorporates into the drawing. The choice of this sort of material emphasises the fact that the works have not grown out of nothing, and that they can never be fully understood simply on the basis of the present context of drawing. With the exception of gouache and oil paint (to which he invariably adds a patina), Borremans usually draws with pencil, watercolour and white ink. Only a very small number of drawings are done only in pencil. His typical shades of brown and grey tints are suited to the ‘old’ patina that is always inherent in the material used for the support. This sense of something past is accentuated even more by the way Borremans chooses to show his works: in modest wooden frames, sometimes set off with white mounts with a perfect diagonal cut. The initiative for this exhibition of Michael Borremans’ drawings came from the Kupferstichkabinett Basel, and it has already been shown at the Kunstmuseum Basel, Museum für Gegenwartskunst. Here at the SMAK, the exhibition has been supplemented by a selection of Borremans’ paintings, which are displayed on the ground floor. In autumn 2005 the exhibition of drawings will move on to the Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland, Ohio (USA). A catalogue will be published to accompany this exhibition, with articles by Anita Haldeman, Peter Doroshenko and Jeffrey D. Grove. The book and the exhibition are coproduced by the Kunstmuseum Basel, Museum für Gegenwartskunst, the Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland, Ohio (USA) and the SMAK in Ghent, Belgium. Michaël Borremans: drawings At first sight the small paintings by Michael Borremans (b. 1963, Geraardsbergen) appear straightforward and convincingly realistic. Nothing could be less true, however. Beneath this seemingly clear imagery and unambiguous content lies an impressive, confusing and odd world which shows itself to be increasingly mixed up the longer one looks at the paintings. On a slightly closer examination of the paintings one realises that the brushstrokes, applied with great talent, not only please the eye but are also intended to provoke the viewer. What one observes here is not a purely narrative scene, but a sort of internal world in which several strange elements complement and/or contradict one another. This internal complexity is already expressed in the choice of the seemingly simple titles that Borremans gives his paintings. Such words as The Pupils, The Barn, The Performance and The Preservation seem simple, but when combined with the image they accompany, give rise to a sort of double deception, which on the one hand can work as a guide and lead to a deeper insight into the painting but on the other can actually encourage the sense of wonder.

In order to understand Michael Borremans’ paintings better, they have to be seen in the context of the ‘humanist’ tradition of painting. One of its most representative artists is Francisco de Goya (1746-1828), who tried to capture the purest state of human existence in disturbing images of the society of the time. Borremans’ handling of this theme is however on a more philosophical and abstract level, where he greatly accentuates the absurdity of human existence. His paintings are frequently populated by almost dehumanised figures who perform absurd minor actions in an entirely imaginary world. This painted environment in which the characters move remains almost completely anonymous and is rarely elaborated in any detail. The only real activity in the painting is the cool grey-white light that focuses on the figures and makes them stand out more. This light, which is created by Borremans’ subtle and almost sensual brush strokes, is halfway between the coolly analytical and the sensitively poetic. He rarely uses white to achieve this, but more often colours ranging from cream to grey. As a result these pictures radiate a warmth that is often to be found in old paintings, but at the same time they suggest a sort of still detachment. The sober and highly distilled composition of the picture area makes it seem that the figures and objects live in a ‘still-life world’, which summons up feelings of melancholy and nostalgia, to some extent similar to the spirit of 19th-century Romantic painting. In contrast to that particular artistic tendency, which pictured the insignificant and doubting human in overwhelming landscapes, Michael Borremans focuses entirely on the human figure and human existence itself. He manipulates his characters in an artificial world which nevertheless appears realistic, thereby actually reducing them to pawns of some sort, who seem to have lost all freedom of choice. By emphasising this artificiality, Borremans also raises questions regarding the medium of painting itself. Although he paints only figuratively, he nevertheless considers painting as a purely artificial art form, in which it is impossible to get close to actual reality. Borremans takes this contrast between reality and fiction to extremes by introducing ‘alien’ elements, which makes it more difficult for the viewer to project realistic or narrative associations into the works. This means that although they are in themselves aesthetic, figurative and thus accessible, as far as their themes are concerned the paintings are actually abstract. Borremans draws inspiration for his work from both older media such as dated photos from the Thirties and Forties, and more recent sources such as films, soaps and television series.

Another fertile source is his fascination for kitsch, typified by the porcelain figures that adorn the windowsills of many Flemish houses. By choosing these media, combined with his extremely sensual, skilful and figurative painting style, Borremans deliberately tries to give his paintings a sort of sexy allure, which greatly increases their attraction for the viewer. The intention is to capture the viewer’s gaze for as long as possible, so that he will automatically start looking for the deeper abstract thematic content of the painting. The choice of subjects rarely has any specific intention but is usually determined by chance. This exhibition of paintings by Michael Borremans runs parallel to the exhibition of his drawings on the first floor. In the course of 2005 the exhibition will move on to the Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art in London and to the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin. This exhibition of drawings was compiled on the initiative of the Kupferstichkabinett Basel, and has already been shown at the Kunstmuseum Basel, Museum für Gegenwartskunst. In autumn 2005 it will also be shown at the Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland, Ohio (USA). The SMAK is therefore the only place where the two exhibitions can be seen at the same time. To accompany this exhibition of paintings, a catalogue is being published with articles by Patrick T. Murphy, Hans Rudolf Reust and Ziba de Weck Ardalan.