Luc Tuymans is a leading exponent of contemporary painting, and one of the key figures in the recent painting ‘boom’.

His work is behind the reintroduction of this medium, and has given a decisive direction to the recent evolution of painting. Tuymans denies the possibility of producing anything original. Everything exists already: this is one of his mottos and the majority of his paintings do in fact arise out of an existing image. In contrast to modernist theories, Tuymans emphasises the notion that meaning is more important than the image. With this in mind he has in recent years touched upon a number of highly charged themes. These range from such relatively topical subjects as the horrors of World War Two to historical subjects going back to a distant past. In each case it involves the transposition of a piece of reality into an image on canvas. In the late eighties he sought a way of depicting the horror of the Holocaust through ‘amnesia and emptiness’. In another series he examined Flemish cultural history on the basis of familiar icons, and in a recent series from 1999 linked up with an age-old painting tradition, the depiction of the fortunes of Christ. For the Biennale, Tuymans has developed a concept for an exhibition that combines a series of new works with smaller groups of existing paintings which will be displayed as a sort of ‘aura’ around the core series.

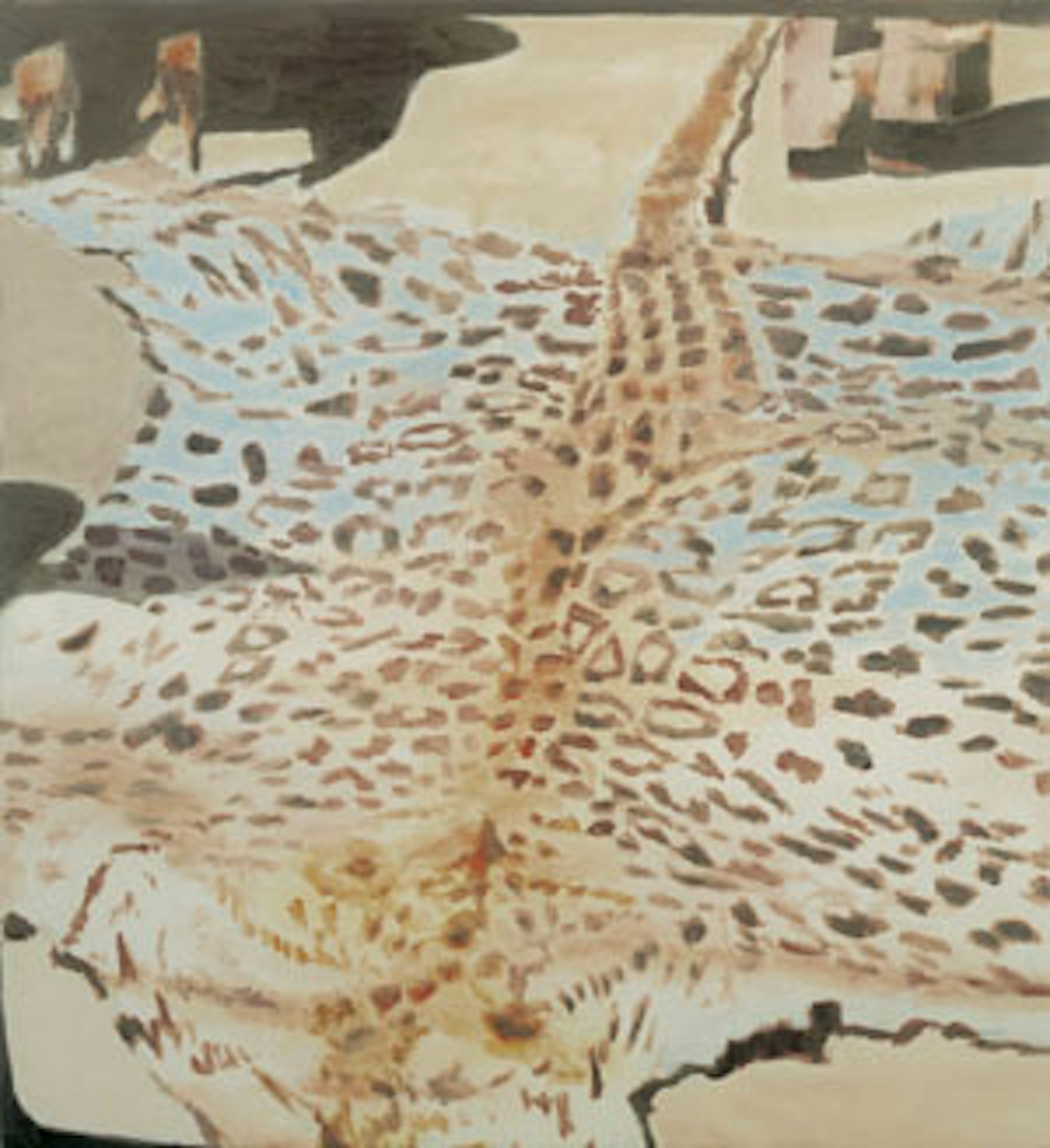

This new series, called ‘Mwana Kitoko - Beautiful White Man’ refers to the colonial issue and more especially to the situation in the Belgian Congo. The topic he wishes to deal with has in recent times once more come to the fore in, among other things, several controversial publications. A commission has also recently been appointed to investigate Belgium’s involvement in the murder of the founder of the Congo National Movement, Patrice Lumumba. For the Biennale, every country is supposed to represent itself in the field of art. Such factors as chauvinism and national pride are however always present under the surface. Tuymans considers it important, in this setting, to show a number of works that refer to the country’s history, and particularly to Belgium’s colonial past. He does not deal directly with socio-political subjects. He tries, rather, to indirectly chart the images associated with the policy of colonial expansion. His intention is by no means to create a linear and cohesive narrative in this cycle of works. The aim is to offer several possible lines of thought by evoking a particular atmosphere. At the same time, these paintings signal another trend which is closely related to such phenomena as globalisation. In this regard, various international exhibitions are making the attempt to integrate artists from ‘elsewhere’, mainly third world countries, into the Western circuit and thereby to open up the domain of art even further. Initiatives like this might easily result in a new form of cultural imperialism, and it would thereby run the risk not being validated on the same terms. In this respect, ‘Mwana Kitoko’ is intended to provide a degree of balance by presenting an exhibition which is very specifically restricted to an episode from national history, but one which still continues to have international consequences today.