For several years now, the name of Jan Van Imschoot is almost inevitable when it comes to young, good Belgian painters.

Not only does Van Imschoot wield an especially fluent, one could say virtuose, handling of the brush, his colours are also perfectly balanced. In addition to this, there is the artist’s choice of often dramatic, strongly narrative subjectmatter which lend the work a dubiously estranging, at times mobid atmosphere.

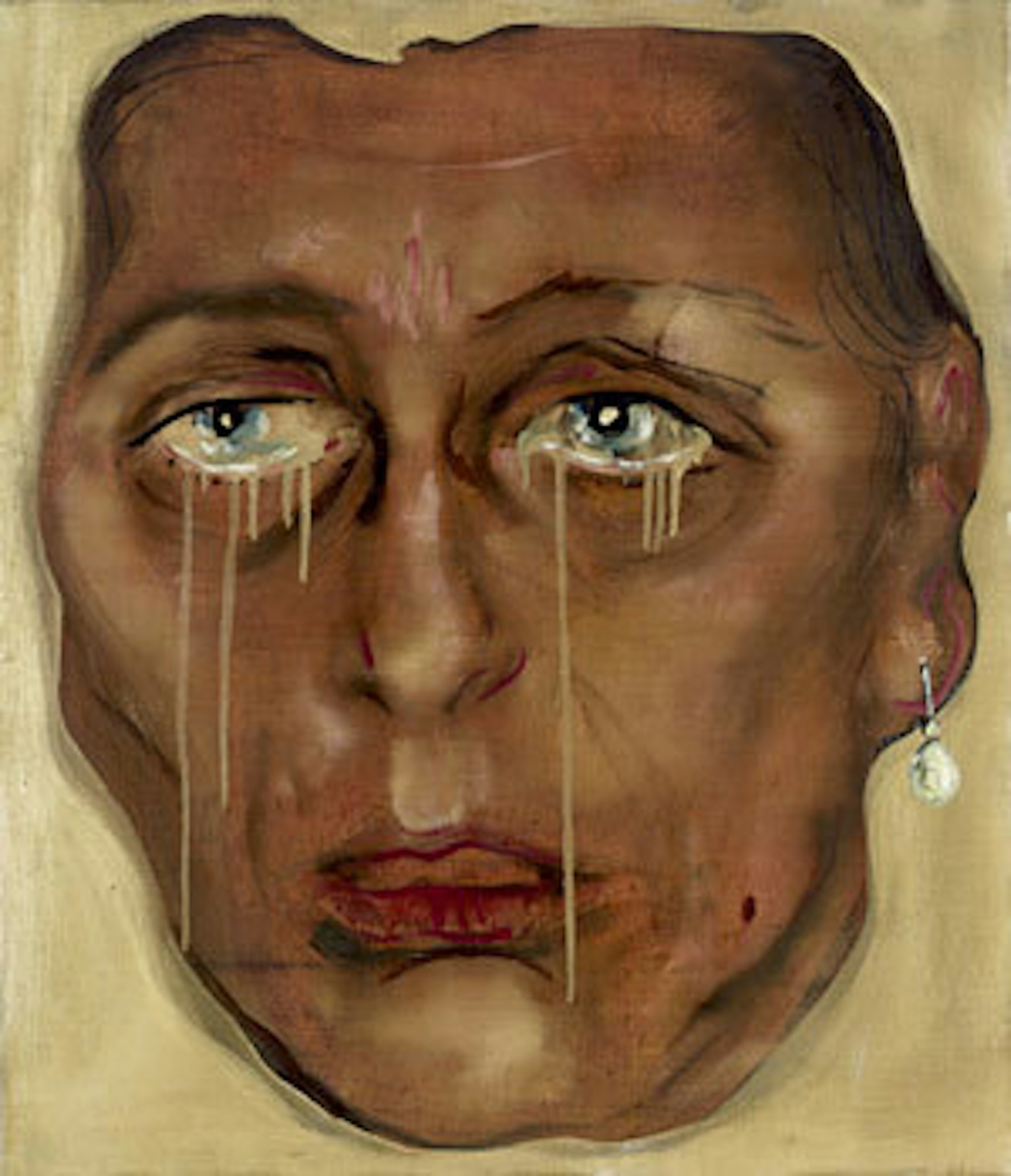

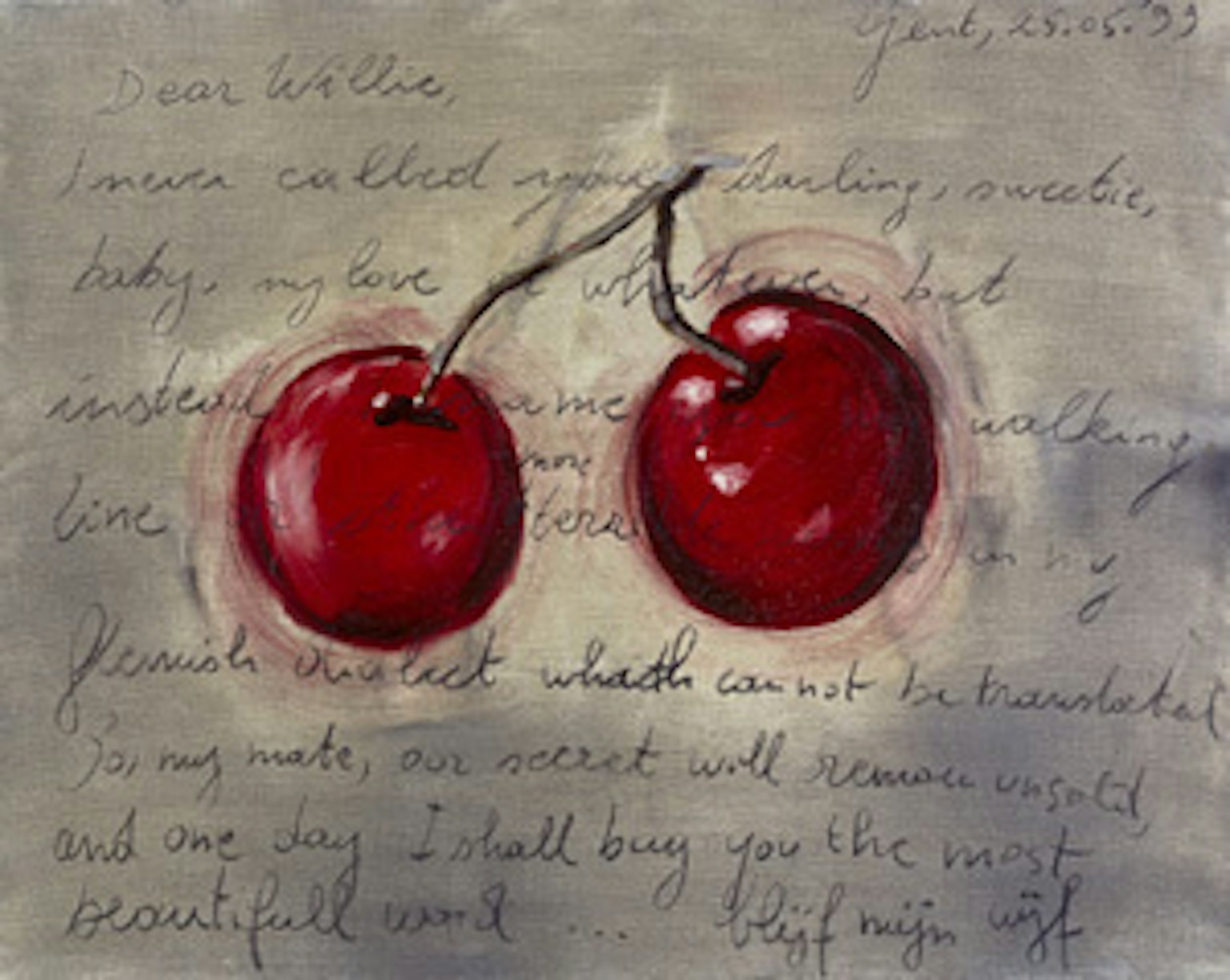

Van Imschoot’s breakthrough came a few years ago when he won the Prize for Culture of the city of Gent, and exhibited a series of paintings of female martyrs in the Vereniging van het Museum voor Hedendaagse Kunst, in Gent. Since then the artist’s oeuvre has strongly evolved. The historically loaded themes, through which he most of all likes to concentrate on the sharp edges of society and the forgotten stories of times past. From the onset his work can be contextualised within the entire history of painting. In the one painting, one can find a strong reminiscence of the sublime exaltedness of Tintoretto, whereas another painting will reveal itself to be leaning closer to the obscurity and distortedness of Goya. One of the constant factors in the artist’s canvases and drawings is the "typically Flemish" sense of humour, read: cynicism and irony. In this he stands in the same line as the Flemish Primitives, painters such as Breughel, Bosch, and later even Joachim Beukelaer and the Seventeenth Century tradition of Vanitas paintings. The viewer needs to approach the paintings in an almost literary manner, in which the word often literally becomes image, and, in reverse, the painting is able to convey a complete story. When the viewer is faced with one of his works, the search that the artist has undertaken in order to arrive at this one image almost becomes palpable. Often the viewer can clearly discern the areas where the artist painted over motifs, text and figures, rarely to conceal or disguise, but often in order to accentuate other parts of the canvas. He renders visible the colours he mixed to achieve that specific atmosphere in the work. This gives the work a rough appearance of sorts, that leads the viewer to assume that the work is unfinished. This is precisely the way Van Imschoot succeeds in strengthening the dichotomous nature of the work, and its mystery. The viewer senses that the artist is not simply interested in producing legible, figurative works, but that he is also seraching for the "right" image. This "image" increasingly figures in van Imschoot’s work, in a number of canvases. These canvases constitute a work in everchanging combinations without ever losing their autonomy as individual "paintings". In his recent work, Van Imschoot seeks a literary contact with the viewer. He widely experiments with different materials and with the active particpation on the part of the viewer. At the same time, the literary qualities of his work are accentuated more and more strongly, without it diminishing the purely visual experience.

Drawings hang alongside paintings; the series are increasingly extended, and the story is enacted on everdeepening levels. The exhibition itself consists of a collection of seven series. While this configuration is not chronologically based, each series is perceived as a key moment in the development of the artist’s oeuvre. It consists especially of recent works which have not yet been exhibitied in Belgium, and of works which will be shown in their entirety for the first time. This is especially the case with "Psychomania", an impressive selection of drawings depicting the vices and virtues of man. Another work is "Lettre de l’etre", a series of 12 portraits of artists, authors, poets, …linked to each other by the central theme "Nole Mi Tangere", the words spoken by the resurrected Christ to Mary of Magdalen when he appeared to het in the form of a gardener. In this the artist’s tendency to work in a more literary way comes to the fore. The paintings only achieve their complete layeredness and meaning when all twelve can be viewed and "read" together. The (auto)biographical aspect in Van Imschoot’s work also plays an important role. With works such as "Confession of a Painter" and "How to sell your wife…" he remains close to his own world, painting the things to which he personally attaches much importance. In close relation to this a criticism of society should be read. Many of his works are signed with the pseudonym "Jean Némar" (the name sounds like the French expression "j’en ai marre", which means: "I am really fed up of it/everything"). This is completely in the trend of the romantic painter who wants to cure the world of all its ills by addressing what is going wrong in a direct and cynical manner. He does this fittingly in "Minuet of a sold skin": nine canvases on which nine tortured and deliberately maimed figures can be seen.