By Sophie Matthys

The key common denominator between S.M.A.K. and the Matthys-Colle Collection is that they both date back to the 1950s, with the collection of contemporary art based on a shared conviction of the importance of artistic innovation. The key difference is that the couple Roger and Hilda Matthys-Colle were then embarking upon a private collection, whilst S.M.A.K., still in an embryonic state at that point, was taking its first steps towards building up the public collection of contemporary art that we know today in Ghent.

But how did it all begin? Their grandson Bruno Matthys, custodian of the Matthys-Colle Foundation, looks back on more than half a century of passion for contemporary art. “Today an automatic link is made between buying something – whether this is an expensive car, antique or artwork – and a long-term investment. These days, collectors often want to play a double game: they purchase something that they find beautiful, whilst simultaneously hoping that its value will subsequently increase. But when my grandparents began to collect art, this was not the case. There was absolutely no assumption that modern art would be worth more ten years later. The word ‘investment’ did not come up. So money or status have never been a motivation for my grandparents, on the contrary.”

How did it all begin?

“When they married in 1946, Roger and Hilda, both doctors, already had an affinity with art thanks to their parents. Roger’s father was an artisan frame maker and a whole host of local artists would visit him. Although they were not big names, the young Roger will nevertheless have had a certain feel for art. My grandmother, Hilda Colle, hailed from the wealthier bourgeoisie, and during that period numerous works by better-known, but generally ‘well-behaved’ artists (such as Emile Claus, Constant Permeke, the Latem School) adorned the walls at home.”

“In the mid-1950s, my grandparents met lawyer and art promoter Karel Geirlandt, with whom they developed a close friendship. It was he who encouraged them to refine their interest in the latest artistic trends and to make the acquaintance of a number of like-minded people in Brussels and Flanders: Hubert and Marie-Thérèse Peeters in West Flanders, Herman and Nicole Daled in Brussels, Anton and Annick Herbert in Ghent, and so on. These were wealthy private collectors who dared to buy the newer art, by figures such as Jan Burssens, Maurice Wyckaert and Reinhoud D’Haese. A work by Jean Brusselmans purchased by the couple was an important pivotal piece in the Matthys-Colle collection.”

Gallery excursions to Paris and New York

“Because my grandparents believed that art did not stop at the banks of the Lys, they soon expanded their horizons, regularly travelling to Paris to visit galleries and discover and buy art. In Paris, which at the time was the European centre of the international art world, they would sometimes visit dozens of galleries in a single day. It should be borne in mind that this was the pre-digital era, so communication took place exclusively by telephone, telex and the good old-fashioned letter. Every purchase was carefully noted down by hand on index cards: name, dimensions, purchase price, etc. These excursions, first to Brussels and Paris, and later also to Venice, New York and Düsseldorf, yielded both a large network and close friendships, including with gallerists such as Ileana Sonnabend and Konrad Fischer.”

‘Every purchase starts with a sense of wonder’

“They only purchased work direct from an artist once. This is hard to imagine, but they bought two works by Christo, a chair and a candlestick, both from 1963, when fame was still a long way off for him. He was short of money and was taking photos to make a living (laughs).”

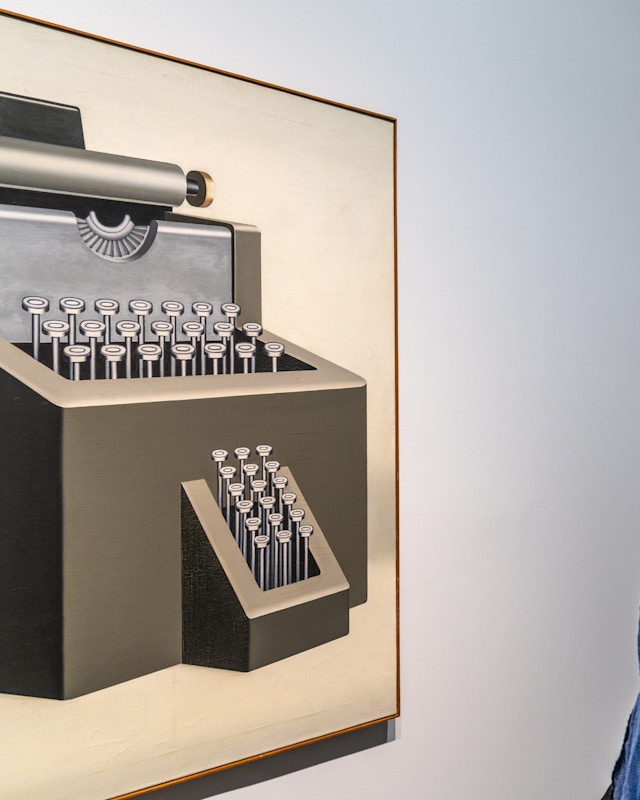

“This also illustrates the fact that my grandparents were predominately buying from young artists who were just starting out and frequently unknown. This alertness that they had is not something that can be taught. Unlike what you often see today, they never solicited advice from others. They followed their intuition and scoured galleries in world cities. They sought out the art and not vice-versa. ‘Every purchase begins with a sense of wonder’, my grandfather would often say. There has to be something that touches you, and that makes you ask what the artist wants to say. Whether or not it is beautiful is of lesser importance.’ This often resulted in highly idiosyncratic choices. The work Sans nature morte by Domenico Gnoli, for example, was revealed to much jeering. My grandparents were ridiculed along the lines of ‘what kind of person buys an empty table as a work of art?’. But history proved them right: the work is currently hanging in Milan at the major Gnoli retrospective.”

‘Everyone was against contemporary art’

“Strangely enough, there was a similar dearth of support for these enthusiastic champions of contemporary art from the Flemish museum world. In the 1950s, the Museum of Fine Arts enforced a rule that only works by artists who had died at least thirty years ago could be exhibited there. No one was concerned with contemporary art. Worse still: contemporary art was sometimes boycotted outright. This lack of progressiveness angered Karel Geirlandt and his friends, who included my grandparents. That was the moment that they founded the Society for the Museum of Contemporary Art, in 1957.”

“It is no coincidence that the first purchases for the Matthys-Colle private collection took place at more or less the same time as the first purchases by the Society for the then Museum of Contemporary Art (V.M.H.K.). In the period that the first contemporary artwork (Louis Van Lint, Geological section, 1958) was bought by V.M.H.K. as the starting point for the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art (M.H.K.), Roger and Hilda Matthys-Colle also purchased their first artwork. Over the years, the Matthys-Colles and the museum would regularly buy work by the same artists. So today at S.M.A.K., works from the same oeuvres are encountering one another afresh.”

No cold investors

“Back to the collection. My grandparents slowly built up an impressive collection with a few big Pop Art works, including pieces by Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol. In order to purchase Big Electric Chair by Andy Warhol (also on display in the exhibition, ed.) they were obliged to sell their beloved work by Jean Brusselmans. Until her dying day, whenever she looked at her Warhol, my grandmother would sigh that it was such a shame she had had to say goodbye to her Brusselmans for it. And I believe that it is here that the essence of art collecting lies: an art collector is, by definition, never happy. They suffer from missed opportunities, regret that they have been unable to buy certain pieces. But there is also jealousy of what another person does have, and the collector does not.”

“The best illustration of why the Matthys-Colles were not cold investors in art is the regret that they always felt when they were obliged to part with something. But also the joy and the pride that they felt when they acquired something new. They quite rightly loved their collection. And yet they regularly sold artworks. Firstly because they needed a budget to buy something new, secondly because they felt that the work no longer fitted into their collection as a whole, and thirdly also because artists sometimes asked them to sell their work to a museum. For example Manet Projekt ’74 by Hans Haacke was sold to the Ludwig Museum in Cologne at the request of the artist himself.”

“Conceptual Art, Minimal Art, Arte Povera, Pop Art, Cobra… It was never my grandparents’ ambition to possess everything in any given art movement. They would regularly decide to relinquish an art movement, chiefly because they had discovered new artists. Early works are where their true interest lay. The Matthys-Colle Collection is not a large collection, but it is an important one, because it includes many pioneering works. Take Andy Warhol, for example. Warhol made numerous cheerful works with which we are all familiar: Marilyn Monroe, Mickey Mouse, the soup cans... But he also made three dark series that were a full-frontal assault on 1960s American society: the Death and Disaster paintings. A series with car accidents, a series with electric chairs, and a series about race riots in which you see photos of police officers attacking black protesters. Of these three series, the Matthys-Colle Collection owns two. And these have enormous contemporary relevance: more than ever, the newspapers are full of topics such as the many traffic deaths, the death penalty and Black Lives Matter. My grandparents bought the less accessible works, but I believe that this makes them all the more interesting.”

The house for the art and not the other way around

“When their townhouse in Ghent literally became too small for their art collection in the late 1960s, the couple decided to build a house in the still heavily-wooded Deurle. This modernist concrete villa was especially constructed to house the collection. Here you once again see their great confidence in young, talented people: in not only artists but also architects. Architect Ivan van Mossevelde was extremely young when he designed the impressive Brutalist villa for them, with a large reception area and wide corridors with white walls that encircled the central patio. From the lighting to the circulation spaces, everything was designed with the collection in mind. Moreover, a number of works were created in situ, including by Sol LeWitt and Niele Toroni.”

“It was the antithesis of a chilly exhibition space. The house became a warm meeting place in which to welcome friends. The cream of the international art scene found their way to Deurle and the parties with Gilbert and George, among others, were the stuff of legend. Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle became good friends of my grandparents.”

‘As a small child I played amongst the artworks’

“As child I was taken to visit my grandparents every Sunday. We would play for hours, roaming around the whole house, where there were no taboos when it came to art. We were encouraged to think about what we saw. We were also allowed to truly experience the artworks, even to touch them sometimes: my sister would walk on her hands across the Carl Andrés on the floor like a kind of acrobat, we would hang upside down on Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cube, and we would balance our way across the Bernd Lohaus on stockinged feet like gymnasts on the beam. And when the Jean Tinguely, the Haim Steinbach or the Dan Flavin were sometimes allowed to be ‘switched on’ and we saw art come to life, it was a riot.”

“And even though we would tear through the long marble corridors past works by Joseph Kosuth and Roy Lichtenstein, and would sometimes secretly move the sticks from Richard Long’s Stick Circle, we still treated this exceptional collection with respect. Even when we were very small, the adults did not constantly have to admonish us to be careful. We instinctively knew not to go and sit in Christo’s Wrapped Chair or Joseph Beuy’s Sledge.”

“In retrospect, it was both absurd for us and yet so normal, but it was a privilege to grow up amongst these phenomenal works. There was no need for us to go to the playground on Sunday afternoon, we had one all to ourselves. And what a playground!”